Mystery Leaf-miners

If you are like us, you are ready for spring! While the weather is starting to warm up, there isn’t much insect activity at this time of year. One insect that is active in the winter is a leaf-mining moth in the genus Rhopobota in the family Tortricidae, the larvae of which are typically leaf-tiers or leaf-rollers. In addition to being active at this time of year, this Rhopobota is of particular interest because it is one of many outstanding mysteries among the leaf-mining micro-moths in North Carolina.

Our mystery moth spends its early caterpillar life in between the upper and lower layers of a leaf, chewing (or “mining”) its way through the inner leaf tissue. This may seem like a somewhat unusual lifestyle, but it is shared with countless species of moths, flies, sawflies, and even beetles. This moth’s mines are found on American Holly (Ilex opaca). You might think that the tough, spiny leaves of American Holly wouldn’t be a particularly attractive meal for a tiny leaf-mining larva, but these small insects easily sidestep the spines, burrowing past the tough outer layer of the leaf.

Leaf-mining moths can often be identified simply by the host plant and the shape of their mines, and our Rhopobota on American Holly has a particularly interesting mine. As you can see in Figure 1, it produces a branching mine that resembles wires in a circuit board. These branches may help protect them from predators, as larvae may be more difficult to locate in convoluted mines (as has been shown in other leaf-mining species). After some time mining (they may produce several mines on different leaves), the tiny caterpillar exits its leaf mine and ties a couple of leaves together with silk, proceeding to feed externally on the leaves from inside its tied-up bunch. It then pupates in the leaf ties, eventually emerging as an adult to start the process again.

If you look at the circuit-board like mines, they appear whitish - which means that as the caterpillars feed, they are not simply pooping behind them, never looking back (like some miners do) - they are instead cleaning out their mines, feeding, but also pooping outside the tunnels they make. Perhaps they must do this, as they spend time advancing and retreating in the same tunnels. In the right-hand photo of Figure 1, you can see what they do with at least some of that poop (scientists call insect poop “frass”) - they make silk pouches at the ends of the mines, and cover those pouches with frass. The larvae sometimes hide in these silk pouches, so birds or other predators looking for prey may look fruitlessly inside the mines, bypassing the pile of frass on the underside, where the caterpillar is hiding.

In addition to their fascinating life history, these moths are of particular interest to us because their identities are still something of a mystery. There are two known species in the genus Rhopobota that feed on holly leaves. Charley Eiseman, a leading expert on leaf-mining insects, initially thought that Rhopobota dietziana was the main species feeding on hollies, but the ones coming from North Carolina seemed to instead be the species Rhopobota finitama. To further confuse matters, individuals from other parts of the state and on different species of holly seemed distinct enough to suggest that we may in fact have more than two species involved, at least one of which has yet to be formally described.

In addition to their fascinating life history, these moths are of particular interest to us because their identities are still something of a mystery. There are two known species in the genus Rhopobota that feed on holly leaves. Charley Eiseman, a leading expert on leaf-mining insects, initially thought that Rhopobota dietziana was the main species feeding on hollies, but the ones coming from North Carolina seemed to instead be the species Rhopobota finitama. To further confuse matters, individuals from other parts of the state and on different species of holly seemed distinct enough to suggest that we may in fact have more than two species involved, at least one of which has yet to be formally described.

Leaf-miner research involves a lot of rearing of adults from larvae. This involves collecting occupied mines or pupae and putting them in vials. Depending on the species and the stage of development, this may also involve periodically providing new leaves, but typically you just have to wait for the adult to come out. One of the major challenges is maintaining a sufficient moisture level so that they don’t dry out, while at the same time keeping fungus from taking over.

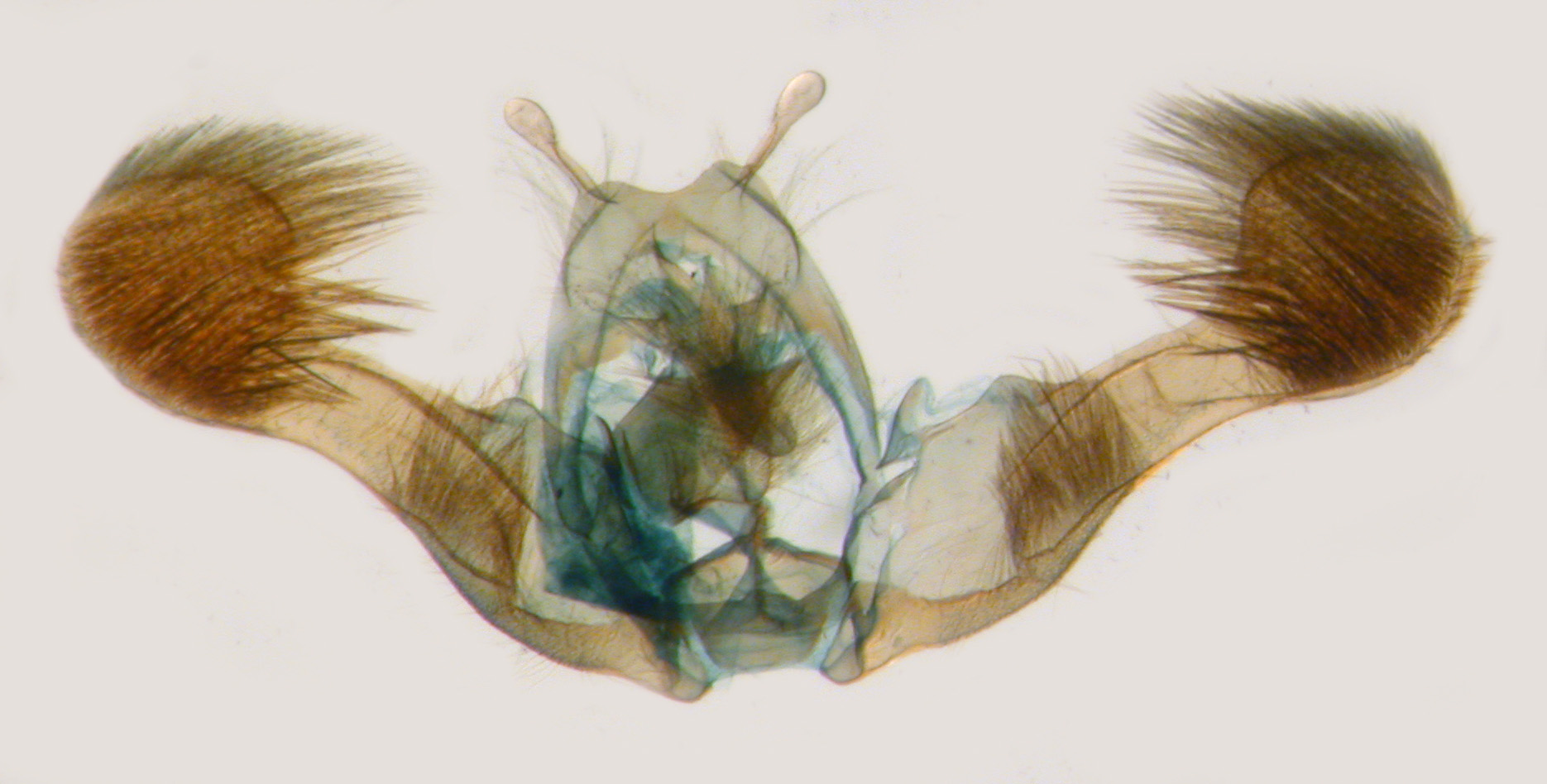

Micro-moths can be quite difficult to identify. Many species are essentially indistinguishable by sight, even with high resolution photos. Interestingly, though species may be outwardly identical, they often have very distinctive internal genitalia. The hypothesis is that males and females fit together like a “lock and key” when they mate, so only members of the same species can mate with one another, maintaining the integrity of a species. Because genitalia are “unique” to each species, dissection is a useful tool for identification. Even so, there is a certain degree of variability within species, so when dealing with multiple potentially undescribed species, dissection alone may not be sufficient. That’s why we often have to rely on DNA barcoding to confirm the identity of these species.

Yet for new species, we must examine DNA from several specimens to see if DNA from each species forms a distinctive “group” (called a clade), separate from other groups. We can then surmise that the different groups are different species, although we may not always know for sure even then. Life is complex, and it is not always simple to unravel the tangled biodiversity we see. We just hope multiple lines of evidence (morphology, DNA, behavior, and ecology) all converge on the same picture, whatever that picture might be.

One of Tracy’s goals for this year is to rear larvae from different holly species in North Carolina, to see if the species can be separated either by their host plant or the region of the state in which they occur. Hopefully we can eventually solve this mystery!

Photos:

- Figure 1 - Tracy Feldman

- Adult image - Mark Shields

- Dissection image - Bo Sullivan

- Leaf mine image - David George